A recent St. Augustine Record article demonstrates how Amendment 6/Marsy’s Law for Florida is being implemented as intended by a supermajority of voters and is working for crime victims.

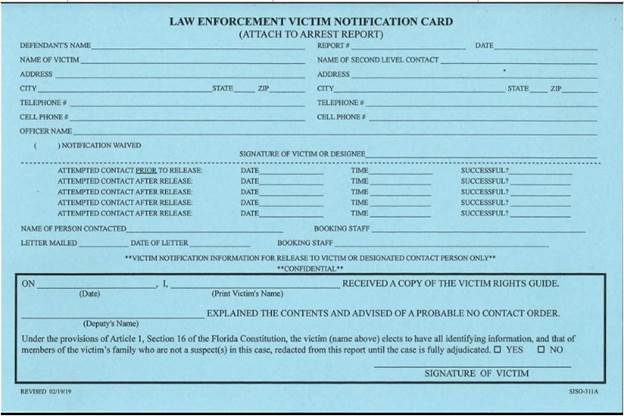

Both the St. Augustine Police Department and St. Johns County Sheriff’s Office are providing victims with cards that notify them of the law and the rights that law provides them. The card also enables them to choose whether or not to have their personally identifiable information – information that could be used to locate or harass them – automatically released to the public.

“This is Marsy’s Law for Florida in action exactly as it should be. Crime victims know what rights are available to them and they have the ability to decide whether to invoke those rights or waive them at a time when reclaiming power over your own life is a critical part of the healing process,” said Jennifer Fennell, Marsy’s Law for Florida spokesperson. “We commend the St. Augustine Police Department and St. Johns County Sheriff’s Office for being proactive and for safeguarding the new constitutional rights of victims.”

According to St. Augustine Police Cmdr. Pat McCaulley, approximately 80 to 85 percent of crime victims are choosing to invoke the right to have their personal information withheld.

Read the full piece below or click here.

Law enforcement weighs in on working with Marsy’s Law

St. Johns County Cheriff’s Office deputies will soon be equipped with victim notification cards that include language added about victims’ rights. Victims can then select to have their information redacted from public records.

By Jared Keever

Law enforcement agencies around the state, and St. Johns County, are grappling with what a constitutional amendment passed by voters last year means for their public records policies and how it will affect them getting information to the residents of their jurisdictions.

Of the county’s three major agencies, the St. Johns County Sheriff’s Office and the St. Augustine Police Department say they are going to leave it up to the victims of the crimes to decide if they want their names and other identifying information redacted from reports.

The St. Augustine Beach Police Department, though, is redacting all victim information without asking.

“There’s nothing in the statute that says they have to invoke it,” Beach Police Cmdr. Lee Ashlock told The Record on Thursday.

He was talking about what was billed as enhanced victims’ rights under the measure commonly referred to as Marsy’s Law.

Passed by voters in the 2018 General Election, the law — which was backed by California billionaire Henry Nicholas, whose sister was murdered in the 1980s — places restrictions on what information law enforcement can release about victims, particularly information like addresses that could be used to identify them.

But many say the language in the new law is too vague as to be understood and interpretations seem to vary widely, while others are looking to the State Legislature to provide clarification.

“There isn’t a whole lot of consensus, I don’t think, on the interpretation,” St. Augustine Police Cmdr. Pat McCaulley said Thursday.

The Florida Times-Union reported earlier this month that the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office is retroactively redacting reports.

Barbara Petersen, president of the First Amendment Foundation, told the Times-Union that, in Leon County, the Sheriff’s Office will only withhold information about a victim upon request, while if the Tallahassee Police Department responds to a crime, they will always withhold information.

Which is how the Beach Police Department is handling it, sort of.

“We put this into effect as soon as it came out,” Ashlock said.

That was mainly to “air on the side of caution” as a smaller agency in a smaller jurisdiction Beach Police Chief Robert Hardwick explained.

Hardwick said it was almost too much to expect a victim of a crime to try to understand after just experiencing something traumatic or upsetting.

“It seems like we are rushing them,” he said.

Instead, his officers are providing the victim with information about the law and leaving it at that.

“We are not trying to guide them,” Hardwick said.

Should the crime garner a lot of media attention with numerous media outlets asking for reports — something Hardwick pointed out doesn’t happen often with his department — his records people can always reach back out to the victim and ask whether their name can be released.

That, he explained, is a far safer way to handle it than potentially violating a victim’s rights because he or she didn’t understand what was being asked at the time the report was filled out.

The St. Augustine Police Department and Sheriff’s Office are taking a slightly softer position.

“We’ve taken the stance that it’s a constitutional amendment,” St. Augustine Police Department’s McCaulley said. “The victims have the opportunity to waive that right.”

Victims are provided a card by the responding officer with information about the law and their rights under it, and they can select whether to have their information withheld or not.

“If I had to guess, I’d say it’s probably 80 to 85 percent that are invoking it,” McCaulley said.

Sheriff David Shoar said Friday his deputies haven’t put it into practice yet, but they too will be using new victim notification cards with language added about victims’ rights.

They can select to have their information redacted and that selection is logged by the deputy.

“If they don’t check either one, we are not going to shield it,” Shoar said.

He discussed generally what he is hearing about how other agencies are applying the law and said withholding addresses or homicide victim information in certain types of cases could hamper investigations and even raised concerns about notifying the public when a crime pattern pops up in a particular neighborhood — something that would be hard to do if addresses can’t be disclosed.

Shoar, who endorsed the law during the election season, called it a “broad swipe” on Friday that is going to cause some problems as people in his position continue to try and figure out how to make it work and what, exactly, it means.

“I mean, what’s next, don’t tell anybody what crimes are being committed?” he said. “I don’t think we thought it through.”