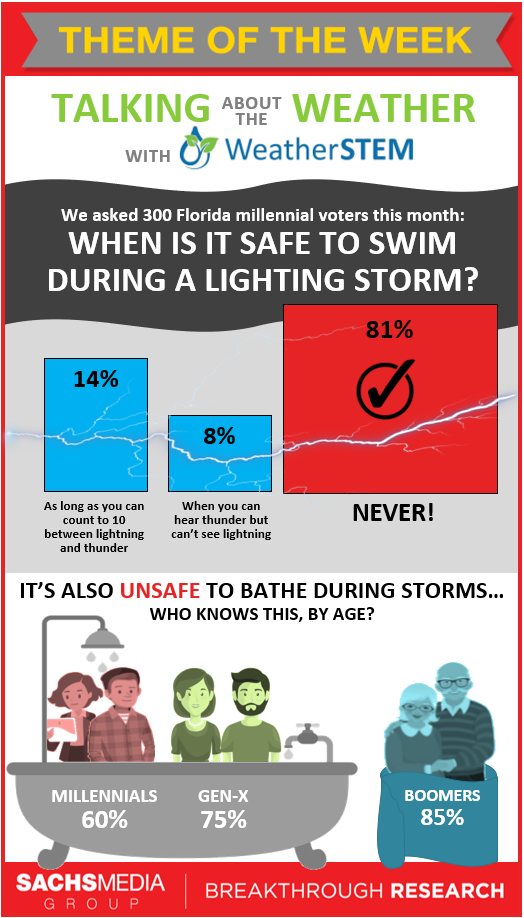

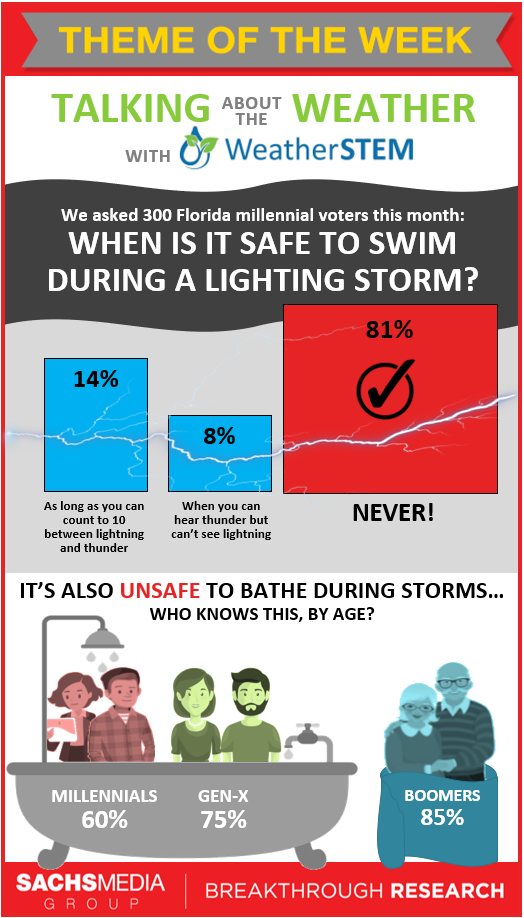

Research infographic describing the percentage of Florida millennials who believe it’s safe to swim during a lightning storm. The bottom diagram displays the beliefs of multiple generations regarding the safety of bathing during storms.

Florida News Straight From the Source

Posted on

Research infographic describing the percentage of Florida millennials who believe it’s safe to swim during a lightning storm. The bottom diagram displays the beliefs of multiple generations regarding the safety of bathing during storms.

Posted on

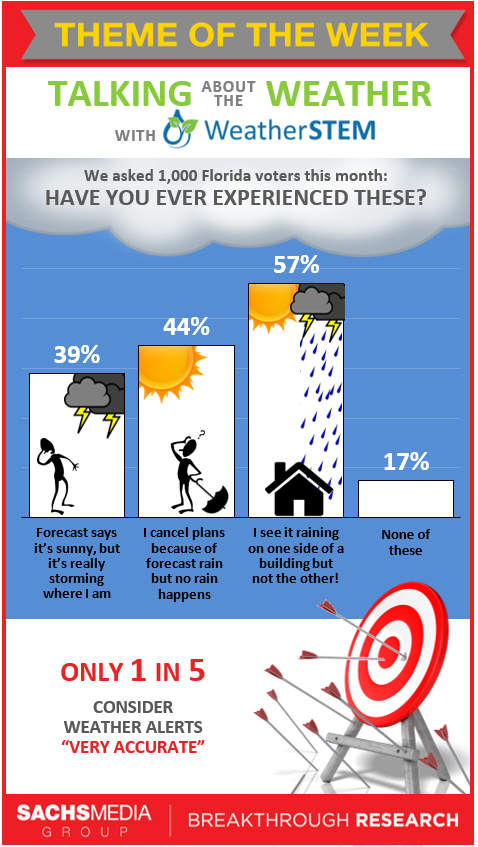

Research infographic describing people’s opinions regarding weather reports in Florida. The bottom statistic claims only one in five people consider weather alerts “very accurate.”

Posted on

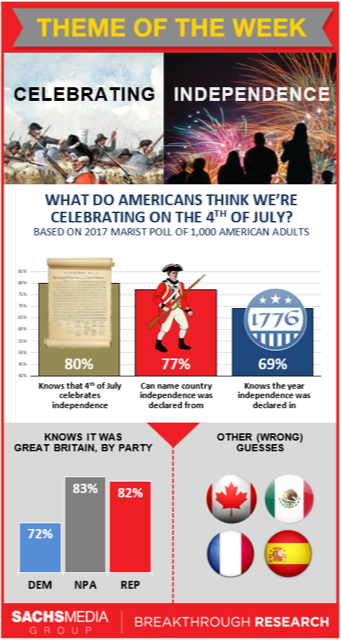

Research infographic describing what Americans think they’re celebrating on the 4th of July and the percentage of each political party that knows we declared independence from Great Britain in 1776.

Posted on

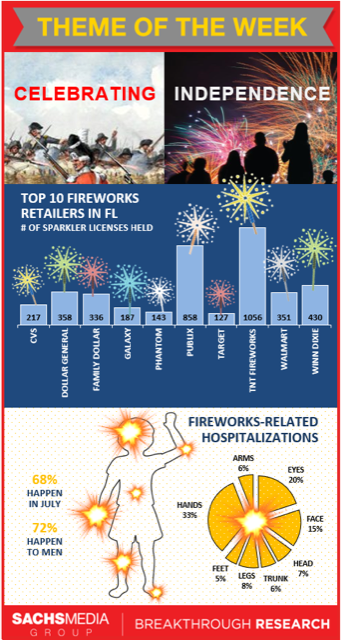

Research infographic describing the top 10 fireworks retailers in Florida, with TNT Fireworks coming in first place. The bottom diagram depicts the number of fireworks-related hospitalizations broken down by month, gender, and body part.

Posted on

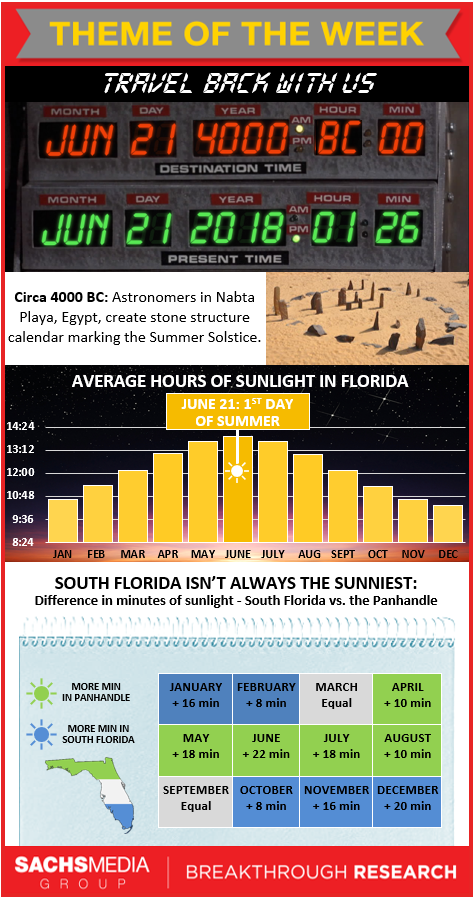

Research infographic describing the history of the Summer Solstice, the average hours of sunlight in Florida, and the difference in minutes of sunlight in South Florida vs. the Panhandle. The lowest diagram indicates the Panhandle having more minutes of sunlight from April to August.

Posted on

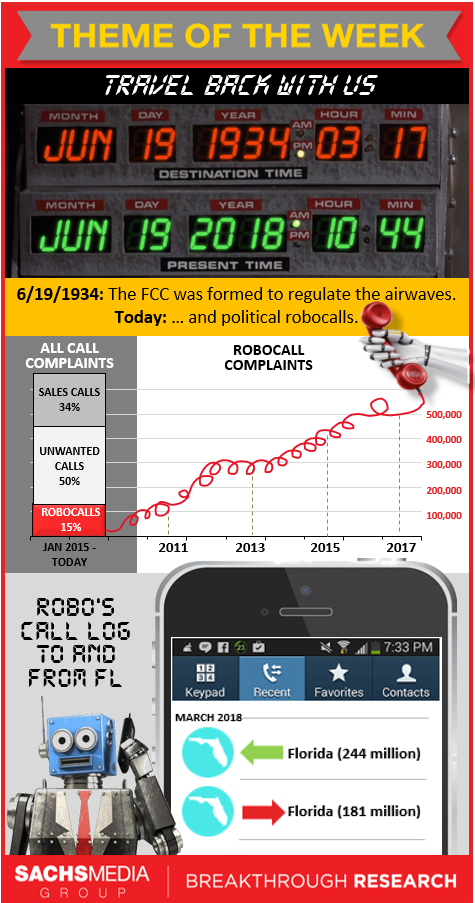

Research infographic describing the increased amount of robocall complaints and the number of robocalls to and from Florida. As of March 2018, Florida made 181 million robocalls and received 244 million robocalls.

Posted on

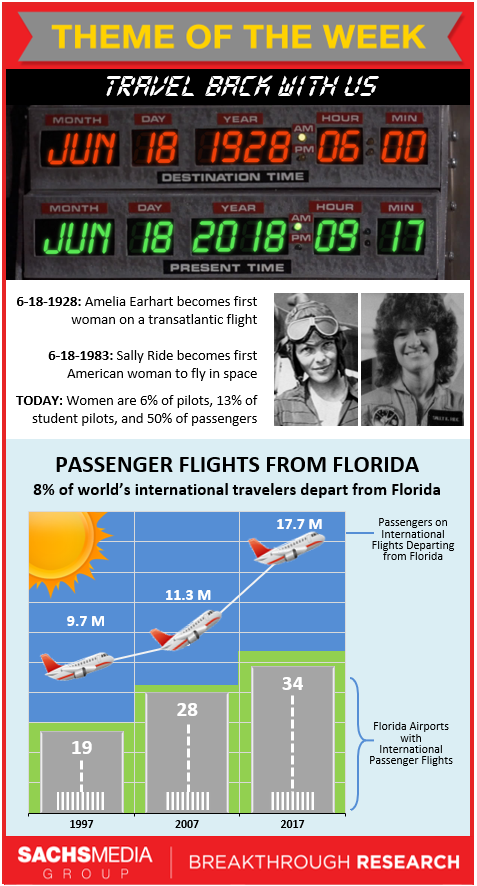

Research infographic describing the history of women in flight and statistics of passenger flights from Florida. The graph indicates the increased number of passengers on international flights departing from Florida over the last 20 years.

Posted on

ORLANDO – UCF faculty brought in $136 million in research funding in 2017, a year that was also marked by national recognition for the number of patents issued to UCF, tech transfer excellence and overall innovation.

Of all the research funding collected, $73.9 million came from federal sources, $41.1 million from private industry and $21 million from state and local government agencies.

The College of Engineering and Computer Science garnered the largest proportion of the total with $33 million, followed by the College of Sciences with $16 million and the Institute for Simulation and Training $14 million.

“We’re off to a good start with funding,” said Elizabeth Klonoff, vice president for research and dean of the College of Graduate Studies. “But where we truly see the impact is in what our researchers are doing to help our communities — from finding new ways to make solar energy systems more efficient and affordable, to improving forecasting methods for sea level rise, to exploring vaccines that have the potential to eradicate disease. It is in this broad array of areas where you can see UCF making a big difference. As we continue to grow our funding, we’ll have more opportunities to have an impact in our Central Florida community and beyond.”

UCF’s research is already getting national attention.

Earlier this year the National Academy of Inventors and Intellectual Property Owners Association announced the University of Central Florida ranks 41st in the world for the number of U.S. patents issued in 2016. From this report, UCF ranks 21st among public universities in the nation.

The recognition is an important one because patents often lead to industrial innovations that impact daily life.

UCF was ranked in the top 25 in the nation in technology transfer, the process of disseminating technology developed as a result of research, along with Columbia University, MIT and Carnegie Mellon University in a report from The Milken Institute, a nonprofit think tank.

U.S. News & World Report’s Best College guide this month (September) also named UCF one of the most innovative universities in the nation, alongside Harvard, Stanford and Duke. UCF was No. 25 out of nearly 1,400 universities and colleges in the nation. UCF also was ranked No. 91 in engineering doctorate programs. Earlier this year, U.S. News & World Report’s Best Graduate Schools of 2018 also recognized 22 UCF programs in the top 100 in their respective fields.

Professors are working on projects that could potentially revolutionize industries and save lives.

For example, Engineering Professor Shawn Putnam is working to change the way electronic devices use and dissipate heat. His work is designed to help keep up with the global demand for faster, more powerful and smaller devices such as computers, radars and lasers. He was awarded a $510,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to support this work.

The Department of Energy this past year supported UCF researchers at the Florida Solar Energy Center and the College of Engineering and Computer Science with almost $4 million of funding to expand their work in solar energy, energy efficiency and improving air quality in homes.

UCF researchers from the College of Medicine, the NanoScience Technology Center, the College of Science and the College of Engineering & Computer Science received more than $1.3 million from the state to come up with ways to combat the Zika virus.

And an assistant professor of philosophy conducted fieldwork at the Dunhuang Mogao Caves along the Silk Road in China this summer. Lanlan Kuang is one of a select group of international scholars with access to the caves which house the largest and most complete repository of Buddhist art, murals and painted sculptures in the world. She will share her findings at conferences around the world including the International Symposium on Cultural and Art Exchanges and Cooperation in Dunhuang, China, in October and at the national conference of Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory in November.

All this research and the funding that comes with it is also important for one other reason.

“Research is fundamental to our mission of educating our students,” Klonoff said. “Hands-on research is essential to preparing the next generation of scientists and engineers, so they can help us with tomorrow’s challenges.”

Posted on

The drill holes left in fossil shells by hunters such as snails and slugs show marine predators have grown steadily bigger and more powerful over time but stuck to picking off small prey, rather than using their added heft to pursue larger quarry, new research shows.

The study, published today in Science, found the percent of shell area drilled by predators increased 67-fold over the past 500 million years, suggesting that the ratio of predatory driller size and tough-shelled prey increased substantially. The study’s authors say the widening gap could be caused by greater numbers and better nutritional value of prey species and perhaps to minimize predators’ vulnerability to their own enemies.

“These drill holes track the rise of bullies: bigger, stronger predators hunting the same size prey their much smaller predecessors did,” said Michal Kowalewski, the Jon L. and Beverly A. Thompson Chair of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida and a study co-author. “What’s exciting about this project is that we found a drilled fossil shell can tell us both the size of the prey and the size of the predator that ate it. This gives us the first glimpse into how the size of predators and prey are related to each other and how this size relation changed through the history of life.”

Predation is a major ecological process in modern ecosystems, but its role in shaping animal evolution has been contentious, Kowalewski said. This study sheds light on predation’s ability to drive evolutionary changes by supporting a critical tenet of the escalation hypothesis: the idea that top-down pressure from increasingly larger and stronger predators helped trigger key evolutionary developments in prey species such as defensive armor, better mobility and stealth tactics like burrowing into the sea floor.

Other than a few rare finds of predator and prey preserved mid-battle, a lack of direct fossil evidence has hindered a clearer understanding of how predators have influenced other species’ evolutionary paths.

Adiel Klompmaker, then a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum, was working on a database of drill holes—the marks left in a shell by a predator such as a snail or slug—when he saw their untapped potential as “smoking gun” evidence of deadly saltwater dramas.

Drilling predators such as snails, slugs, octopuses and beetles penetrate their prey’s protective skeleton and eat the soft flesh inside, leaving behind a telltale hole in the shell. Trillions of these drill holes exist in the fossil record, providing valuable information about predation over millions of years. But while drill holes have been used extensively to explore questions about the intensity of predation, Klompmaker realized they could also shed light on predator-prey size ratios.

Just as a bullet hole indicates the caliber of gun fired, a drill hole points to the size of the predator that created it—regardless of what kind of animal it was. By compiling these hole sizes, researchers can gain insights into 500 million years of predator-prey interactions.

“Finding direct evidence of behavior in the fossil record can be difficult, certainly in comparison to all animal behavior we can simply observe today,” said Klompmaker, the study’s lead author and now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, where he conducted most of the research. “Drill holes in shells are an exception to this rule.”

To determine whether drill hole size is a good predictor of the size of the animal that made it, the researchers compiled 556 measurements of predator sizes and the diameter of the holes they produced. The measurements spanned 14 families and five phyla of drillers, both terrestrial and marine: mollusks, arthropods, nematodes, Cercozoa (parasitic protists) and Foraminifera (amoeboid protists). The team found a strong correlation between predator size and the diameter of drill holes.

“It’s similar to how the size of your arm is related to your height and overall body mass,” Kowalewski said. “It’s not a perfect correlation, but there is a very strong relation between the two.”

The team then used data compiled from 6,943 drilled animals representing many fossil species to examine trends in the size of drill holes, prey size and predator-prey size ratios, starting in the Cambrian Period—when most marine organisms appeared—and running to the present.

Despite growing bigger, predators may not have needed to switch to larger targets because prey became more nutritious through time, the researchers said. In the Paleozoic Era, about 541 million to 252 million years ago, clam-like organisms known as brachiopods were the most common prey available. But predators gained few nutrients from brachiopods and gradually transitioned to mollusks, similarly-sized but meatier prey that became abundant in oceans after the Paleozoic.

“In modern oceans, a predator can gain quite a bit of food from eating a small animal,” Kowalewski said. “This was not the case 500 million years ago when much less fleshy prey items were on the menu. Ancient small prey could only satisfy the needs of small predators.”

Another factor circles back to the escalation hypothesis: As predation ramped up, predators themselves were increasingly vulnerable to their own predators. Chasing, hunting and drilling into prey creates a window of time when predators are exposed to their own enemies, such as crabs and fish, Klompmaker said. Pursuing small, easy prey could lessen the risk to predators themselves.

Seth Finnegan of the University of California, Berkeley and John Huntley of the University of Missouri also co-authored the study.

Funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation, the Packard Foundation and the Jon L. and Beverly A. Thompson Endowment Fund.

Sources:

Michal Kowalewski, [email protected]

Adiel Klompmaker, [email protected]

Writer:

Natalie van Hoose, 352-273-1922, [email protected]

Posted on

For decades, aspirin has been widely used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular problems. Now, a team led by a University of Florida Health researcher has found that aspirin may provide little or no benefit for certain patients who have plaque buildup in their arteries.

Aspirin is effective in treating strokes and heart attacks by reducing blood clots. The researchers tracked the health histories of over 33,000 patients with atherosclerosis — narrowed, hardened arteries — and determined that aspirin is marginally beneficial for those who have had a previous heart attack, stroke or other blood-flow issues involving arteries. However, among atherosclerosis patients with no prior heart attack or stroke, aspirin had no apparent benefit. The findings were published May 18 in the journal Clinical Cardiology.

Because the findings are observational, further study that includes clinical trials are needed before definitively declaring that aspirin has little or no effect on certain atherosclerosis patients, said Anthony Bavry, M.D., an associate professor in the UF College of Medicine’s department of medicine and a cardiologist at the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainesville.

“Aspirin therapy is widely used and embraced by cardiologists and general practitioners around the world. This takes a bit of the luster off the use of aspirin,” Bavry said.

Bavry said the findings do not undercut aspirin’s vital role in more immediate situations: If a heart attack or stroke is underway or suspected, patients should still take aspirin as a treatment measure.

“The benefit of aspirin is still maintained in acute events like a heart attack or a stroke,” he said.

Among more than 21,000 patients who had a previous heart attack or stroke, researchers found that the risk of subsequent cardiovascular death, heart attack or stroke was marginally lower among aspirin users.

For those atherosclerosis patients who had not experienced a heart attack or stroke, aspirin appeared to have no effect. The risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack and stroke was 10.7 percent among aspirin users and 10.5 percent for non-users.

Patients who enrolled in the nationwide study were at least 45 years old with coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease or peripheral vascular disease. Their medical data were collected between late 2003 and mid-2009.

The researchers did identify one group that got some benefit from aspirin — people who had a coronary bypass or stent but no history of stroke, heart attack or arterial blood-flow condition. Those patients should clearly stay on an aspirin regimen, Bavry said. Bavry said discerning aspirin’s effectiveness for various patients is also important because the medicine can create complications, including gastrointestinal bleeding and, less frequently, bleeding in the brain. Because of insufficient data, the current study wasn’t able to address the extent of aspirin’s role in bleeding cases.

“The cardiology community needs to appreciate that aspirin deserves ongoing study. There are many individuals who may not be deriving a benefit from aspirin. If we can identify those patients and spare them from aspirin, we’re doing a good thing,” he said.

The current findings are the second time this year that Bavry and his collaborators have published research about the apparent ineffectiveness of aspirin therapy. In April, the group showed that the drug may not provide cardiovascular benefits for people with peripheral vascular disease, which causes narrowed arteries and reduced blood flow to the limbs.

Bavry also cautioned patients with atherosclerosis or peripheral vascular disease not to quit aspirin therapy on their own. Instead, they should discuss the matter with their physician, he said.

Scientists from France, England and Harvard Medical School collaborated on the research. Patient data were derived from The Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health registry, which was sponsored by the Waksman Foundation and pharmaceutical companies Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Copyright © 2021

Terms & Conditions